An old train ride sits unused as people wander inside the old compartments, a tall looming ferris wheel in the distance. The old bells and whistles of the attractions can be heard as mannequins ride around in the carts.

Monitors play short videos telling the stories of past traveling shows, immersing the audience into the world of vintage entertainment.

Just two hours from Disney World in Riverview, Florida, is a hidden gem with a plethora of history all about the original American carnival and circus industry.

The International Independent Showmen’s Museum has been a home and archive for show people for more than four generations, housing artifacts, photographs, paintings and an assortment of memorabilia from a century of entertainment.

The history of traveling shows across the United States is almost as old as the country itself. The first circus was owned by Bill Rickets in 1793. These early traveling shows included theater troupes in small wagons, which would later transition into large train cars traversing the entire United States.

One of the first traveling shows was the Wild West Show at the turn of the 20th century, featuring legends such as Buffalo Bill, Chief Sitting Bull and Annie Oakley.

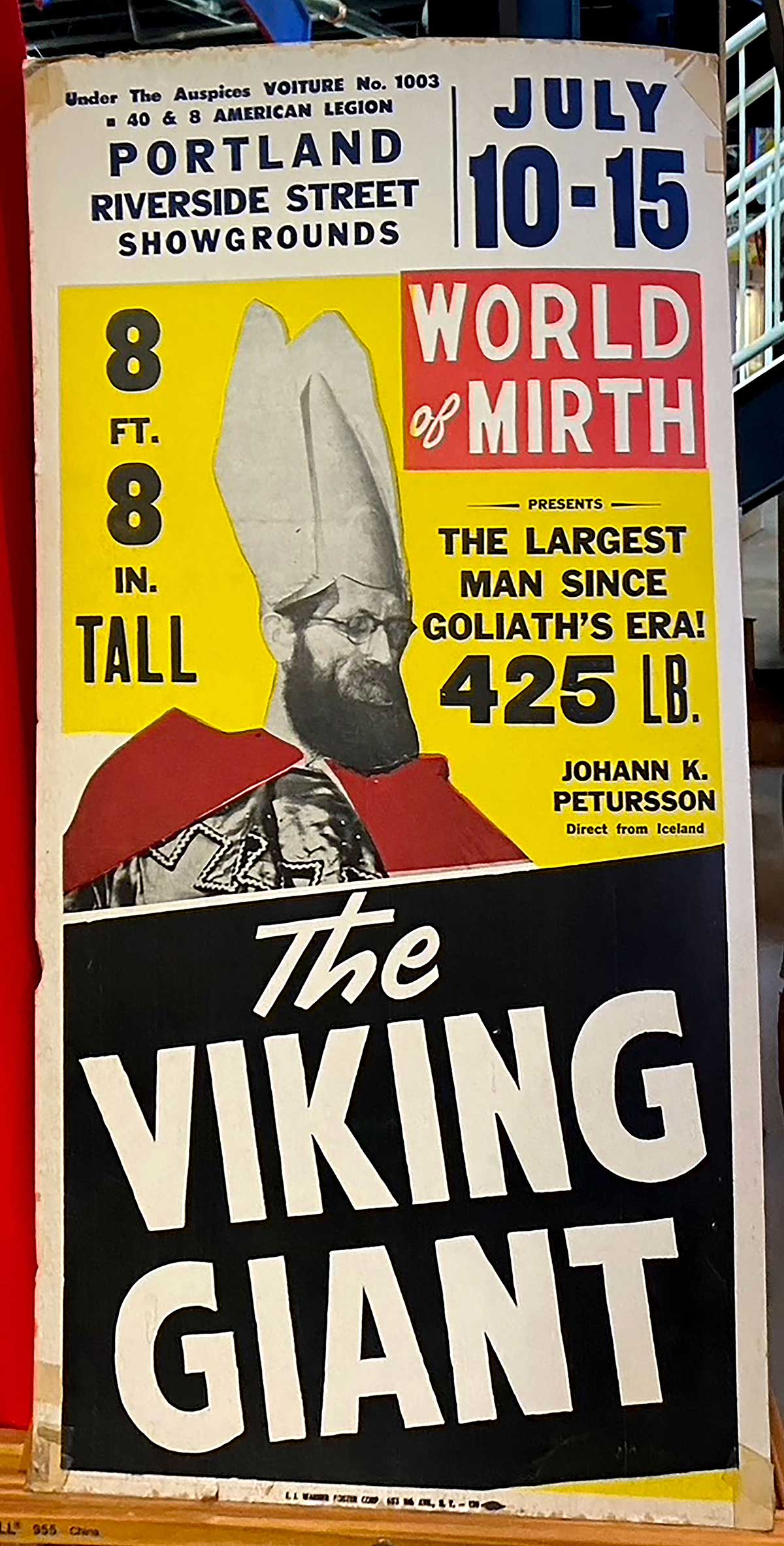

With traveling shows, came traveling circuses. Popular companies at the time include the Barnum and Bailey Circus, which featured people labeled as “freaks,” depicting them as “nature’s mistakes.” These include “The Viking Giant,” “The Two-Headed Baby,” “The Monkey Girl,” “The Living Half Girl,” and “The Four-Legged Girl.”

Johann Petursson, or The Viking Giant, was the tallest Icelandic man, standing at about 8-feet, 8-inches. He took on alter egos on stage such as “Olaf” and “Der Nordische Riese Olaf” which translates to “The Viking Giant.” He ended up touring with the Barnum and Bailey circus for their 1948 season.

The Two-Headed Baby was usually a side-show piece, where showrunners would present a human fetus with two heads embalmed in a glass jar of formaldehyde. They were sometimes sold to hospitals or to traveling carnival. The practice was later disbanded in the 1950s and 1960s as an unlawful practice.

People with deformities or rare conditions also made appearances in these shows.

The “Monkey Girl,” who’s real name was Percilla, was born with hypertrichosis, a rare condition which causes excessive hair to grow over the face and body. This gave her a full beard as a baby, which brought her into the sideshow business at a young age.

The “Half Girl,” Berniece Evelyn “Jeanie” Smith, was born without legs and her arms were twisted. Her parents put her on stage starting when she was three, where she would perform acrobatic acts.

The “Four-Legged Girl”, or Ashley, has a rare form of conjoined twinning known as dipygus, where a variation of parasitic twins gave her two complete bodies from the waist down. The four legs she has were from an unborn twin which was absorbed into Ashley’s body during her fetal development. She is still alive today, but no longer performs in public.

Along with the traveling circus, the Showmen’s Museum shows off many donated pieces of old-fashioned carnival rides including bumper cars, carousels, penny arcades and a ferris wheel.

The Conderman Ferris Wheel is the tallest exhibit. It was built in 1903 and donated by the Wheelock Family in 1988. Patrons cannot ride the attraction, but can admire the mannequins in many of its carts.

These traveling carnivals would supply their own power, using mules, horses and eventually transitioning to portable steam dynamos. From the 1920s to the 1960s, many of them would also use junction boxes which connected all of the shows together on a single power grid. Today, bigger carnivals use as much power as a small city.

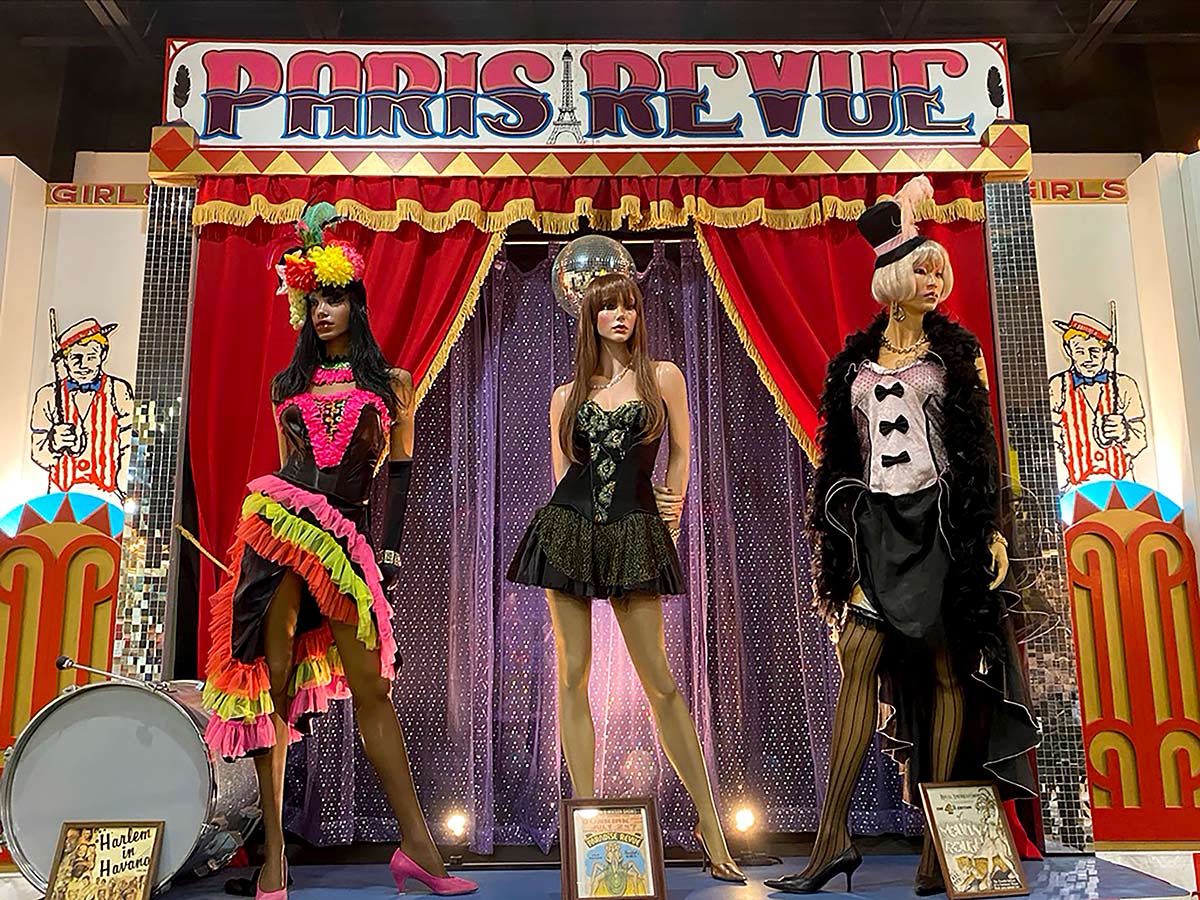

Around the pavilion, there are also different videos to watch, which include the first silent film, “The Great Train Robbery,” and miniature documentaries about shows such as The Wild West Show and The Motordome. Mannequins are posed around the room in accurate costumes to the time period.

While the acts would now be considered insensitive, giving the public access to this information and historical context is important.

Seeing these artifacts and learning about the history of the circus is eye-opening, especially for fans of the movie, “The Greatest Showman.” Watching Hugh Jackman act as the now considered controversial figure of P.T. Barnum, sparks interest in the real stories now brought to life by the museum.

The International Independent Showmen’s Museum is open every Saturday and Sunday from noon to 5 p.m. Admission for adults is $15, $10 for children with a school ID, and children under 10 are free.

For information, visit showmens museum.org.