LU’s Chadwick publishes biography of Dubuffet

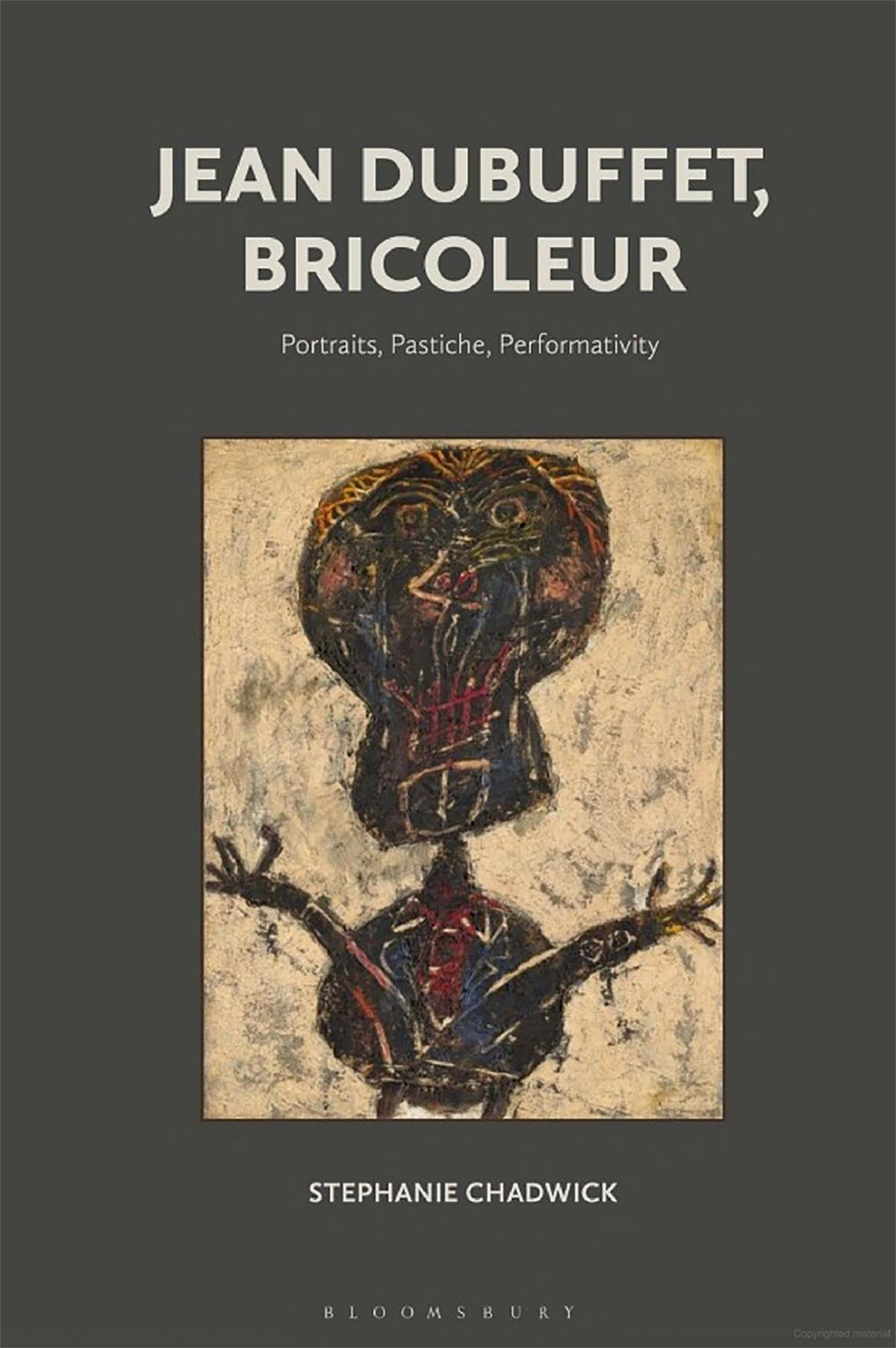

Stephanie Chadwick, Lamar University’s chair of the department of art and design, has released “Jean Dubuffet, Bricoleur: Portraits, Pastiche, Performativity,” a biography of the French late modern and contemporary artist.

“Even though the title is a little bit specialized, I think it’s pretty open to general readers, not just art historians or artists,” she said. “He is best known for his work of the post-World War II period, but he really produced work between the 1940s and the 1980s.”

Dubuffet created different kinds of paintings, including a body of portraits, almost 200, between 1946 and 1947, Chadwick said.

“Some of them look like graffiti if they're done in pencil or ink, and then a lot of them are done in paint, and it looks really kind of muddy or fleshy,” she said. “They range from funny to frightening, which got me curious.”

Chadwick said the word “bricoleur” in the book’s title is synonymous with tinker or handyman, referring to someone who makes things using miscellaneous art.

“I'm using that idea of tinkering as it relates to forms of collage or assemblage, because Dubuffet was looking at a lot of different images and then combining them into his own style,” she said. “Pastiche is another one of these words that means an artist who's emulating other art forms.

“The reason that I use Performativity in the title is because a lot of the subjects deal with performance that was going on with Dubuffet and the people he painted. He (drew them) performing their own identities. That's what performativity is all about. It's this idea that the actions you take, the things you say, and the representations you create, shape your identity and your experience.”

Chadwick said Dubuffet’s paintings inspired her dissertation at Rice University, and she has been developing the book for almost 10 years. The book features more than 60 images with 25 from the Dubuffet Foundation. Acquiring the rights to the images was a long process, she said.

“I had to contact people from institutions all around Europe and the United States,” she said. “The comparative images that I got came from different rights holders and different museums. I was contacting people in New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Paris, Switzerland, Germany, London and even Spain. It’s been a lot of legwork and that's part of what I've been doing the last two years.

“Getting access to all kinds of different research libraries, doing most of the research, even just getting permission sometimes to access some of the archival materials was challenging, but it was fun.”

Chadwick said the book looks not just at Dubuffet’s art, but also his life and the relationships he had with other artists.

“I do a lot of discussion of the art itself, but I contextualize that within Dubuffet’s life, like what was he doing before World War II? What kind of connections did he make?” she said. “A lot of people talk about Dubuffet as a bridge between the Surrealism of the 1920s and ’30s and the art of post-World War II that was happening from the ’40s all the way up until the end of the 20th century.”

Chadwick said Dubuffet’s style, post-WWII, appears gritty and confrontational because of the human mindset at the time and how most people in the arts and humanities felt that the war demonstrated the failure of Western humanism.

“They were saying, ‘This is all a pile of rubble now, we just have all this kind of really gritty materials to work with, let's start over and do something radically new,’” she said. “That's why I chose the portraits. When you look at them, you're seeing depictions of other human beings, and each one of those people has a collection of stories behind them.”

Along with his portraits, Chadwick said Dubuffet looked at outsider art — people who were not trained artists — created in France and other parts of Europe.

“There's a lot of comparative imagery between what Dubuffet was doing and ways that he was emulating these other art forms,” she said. “It’s kind of tricky because he was always claiming his art was so original. He was looking at a lot of different forms of art and synthesizing them into what became his own styles.”

Chadwick said the amount of material available made it hard to narrow down. Every summer, she would make one or two trips for research. One of the best leads was a book by a dance group from the 1930s called The Archive International Diva Dolls.

“The group was visiting Indonesia and they were filming, photographin, and collecting a lot of the artifacts that I was looking at,” she said. “I got to look at a lot of different kinds of art forms and realize how there are so many intersections between visual arts, theatre and dance.”

Writing the book has impacted Chadwick’s teaching, she said.

“When I teach students, I'm always telling them that the more you look at a picture, whether it's a painting or a photograph, the more you see,” she said. “If you take a casual glance, you're going to get a certain level of information. But if you look at it closer, a couple of times, you're going to start to get more information. This (project) was a great teacher for me in that way, because the experience taught me so much. Putting it all together gets more of a rich history.”

Although the book stemmed from Chadwick’s dissertation, she said there are clear differences between the two.

“The dissertation was a giant assignment and the book needed to be something interesting that people want to read,” she said. “I've just been refining the research, the writing, and getting the image permissions. That's where I really learned how to take something that was an assignment with a lot of factual information that isn't that interesting — and figure out what to keep and get rid of — so it becomes an actual book with chapters that hopefully have an engaging subject.”

For more information, visit bloomsbury.com/us/jean-dubuffet-bricoleur.