“I think it is quite unusual to see Russian art in the West, outside of New York and some other major cities,” Richard Gachot, Lamar University associate professor of art and design, said.

Gachot is curating “Russian Art and Soviet Design,” an exhibition of more than 50 pieces that contrasts two periods of 20th century Russian art: Imperial Fine art and Soviet Design. The show will be on display Oct. 3 through Nov. 14 in the Dishman Art Museum. The exhibit is open to the public, with a capacity of 10 people at a time.

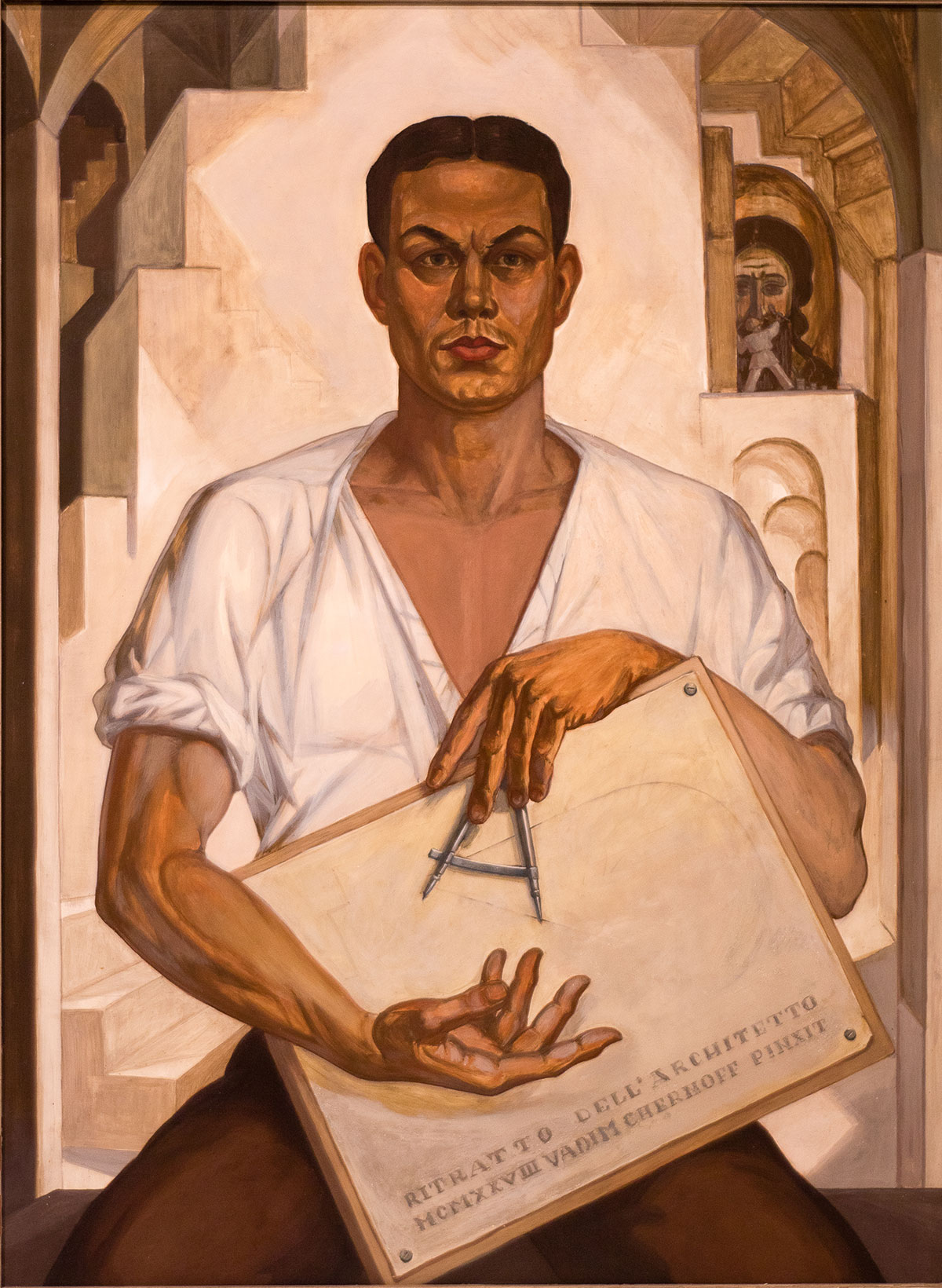

“Russian Imperial art embodied traditional media — painting, sculpture and drawing — with themes drawn from the Orthodox church, Slavic history, folklore and the nascent avant-garde ranging from the Wanderers to the Ballets Russe,” Gachot said. “This art, handmade and one of a kind, was rejected after the 1917 October Revolution by the Bolsheviks and Lenin, as “bourgeois decadence” to be replaced with an ‘art for the masses.’”

Gachot said the latter took the form graphic art, including posters and magazine designs.

“Industrial design celebrating domesticity and childhood,” he said. “Finally, ideological themes which celebrated the collective and greater causes of the Soviet people, like work, sports and space exploration.

“Soviet art and design started almost tabula rasa with some influence from cubism and futurism. However, the work of the Constructivist movements in the 1920s were probably among some of the most radical design work of the 20th century, for example, the Stenberg Brothers’ graphic design work. After a return to ‘Soviet Realism’ in the 1930s, fine art becomes an empty propaganda vessel. However, design continues in its own subtle innovative way. Look at the form of the Sputnik satellite, remarkable in both its beauty and simplicity. The humor of the classic Nevalyashka roly-poly doll. The graphic design of both caviar containers and candy wrappers.”

Gachot said much of the work in the show was given to his grandfather by fellow Russian émigré artists he befriended while in the U.S.A. and Europe.

“My grandfather, Boris I. Riaboff, was born in 1896 in Sarapul, Russia,” he said. “In 1913, he graduated from the Institute of Civil Engineers in Saint Petersburg, Russia. He later fought in World War One as a captain in the Tsar's army. As the (Russian) civil war broke out in 1918, he was told by his commanding officers to flee Russia and start a new life elsewhere. He left from the far eastern city of Vladivostok and stayed in both Mexico and Cuba before he emigrated to the United States, arriving in NYC in 1921.”

Riaboff entered the University of Pennsylvania and earned a master’s degree in architecture.

“He loved to paint, and his favorite medium was watercolor,” Gachot said. “It is said that after helping win a major battle in Russia, he was rewarded with a one-week leave, in which he chose to paint the countryside of the Caucasus rather than take a trip back to Moscow or Petersburg.

“He did very well at the University of Pennsylvania and received a traveling scholarship upon graduation, subsequently visiting Spain, France and Italy. Some of his sketches from this trip are in the show. He moved to New York City in the early 1930s to work in a large architecture firm, and eventually settled in a small Russian émigré community in Sea Cliff, New York where he built and hand-carved a Russian Orthodox Church, Our Lady of Kazan, in 1940.”

Gachot said his grandfather’s work inspired him to become an artist.

“I remember seeing his work as a child, as well as the work of his friend, a fellow Russian émigré architect named Nicholas Vassilieve, and being fascinated with both,” Gachot said. “I later wrote a book on Vassilieve and I went to Columbia University to study architecture, thanks to my grandfather's inspiration.”

Gachot said he did not collect Soviet design until fairly recently.

“My wife was born in the USSR and after several trips to Russia to visit her family, I became interested in Soviet architecture and design,” he said. “Though my grandfather may not have approved, I find there were very rich periods of work in the early Soviet avant-garde in the 1920s and again after WWII, a very subtle, low key but rich design period we are just beginning to appreciate.”

The Dishman Art Museum is located at 1030 East Lavaca St. on the Lamar University campus. Hours are Monday- Friday, 10 a.m. - 5 p.m.

For more information, call 409-880-8137, or visit lamar.edu/dishman. Visitor guidelines are also listed on the site.