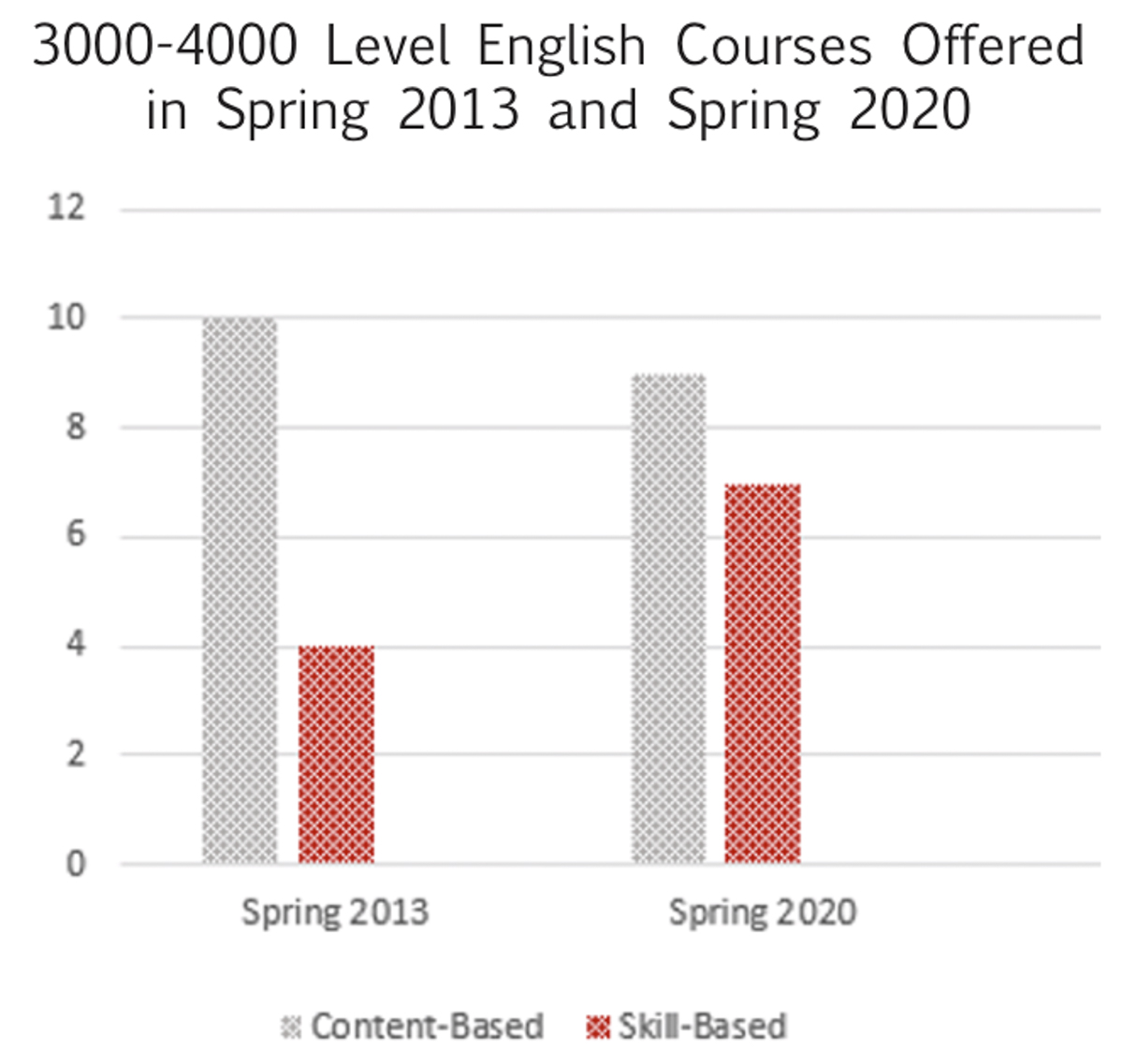

Emphasis on skill-based courses rather than literature

The department of English and modern languages has shifted its course offerings, reducing the number of literature courses in favor of a more skill-based approach.

“We’ve shifted from more of a content-based curriculum to a skill-based curriculum,” James Sanderson, English and modern languages department chair, said. “We hope that what we say in our outcomes that we put in our syllabi is what students are going to be able to achieve when they graduate.”

Sanderson said there has been criticism of decreasing literature-based courses.

“We’re trying to adapt now,” he said. “There are schools of thought that say one of the problems with the humanities is that we’re not keeping up the traditions, that we’re not enforcing more rigorous thought by having students read the best there is. It’s more of the canonical argument. So, the humanities have lost their rigor. I can see both sides of the fence.”

Courses that have not been taught since before the spring semester of 2018 include modern fiction, poetic analysis, and issues in language and literature. Sanderson said the shift is not the only factor in choosing which courses to cut.

“The state has a requirement that if you don’t teach a course in three years, it goes away,” he said. “As far as students, we try to guess what students might be interested in. We ask students once in a while, but sometimes we get it right, sometimes we don’t. And a lot depends upon what the faculty expertise is in.

“Over time, we’ve accumulated all these courses and we just don’t have the faculty to teach all of them. Also, for a department like ours, at our size at Lamar University, we can’t do everything that you might lump up under English.”

While Sanderson believes this shift will benefit students today, other faculty members, such as English professor Lloyd Daigrepont, fear that English majors will miss out on learning literature.

“We’ve got courses now that you can take and structure a degree plan where you would take a lot of creative writing,” Daigrepont said. “What always gets me about that, is I’m afraid that that’s going to take away from the knowledge of literature. I’m always quick to point out that people like C.S. Lewis and Tolkien were professors of literature, but they wrote creatively.”

Though he sees the benefits of skill-based courses, Daigrepont said he still wants students to have exposure to and understand different types of literature.

“These changes are training students for the world that’s out there,” he said. “I’d really be sorry if somebody got an undergraduate degree here, or especially went on to get a master’s degree, and never took Shakespeare. It’s possible to do that. I would like all the students that we have as majors to have literature courses in every area. It may be just a survey course where you take the two-part British survey where you go from Anglo Saxon to 1800, and from 1800 to the modern period. At least you get a smattering and you kind of know how the literature develops.”

English professor Adam Nemmers said that the literature and content-based courses already equip students with valuable skills.

“It depends on what we mean by equipping,” he said. “I think a lot of English faculty and English departments think that we are equipping students to be better people, better thinkers, better readers, better citizens. By reading literature, specifically, you open up your horizons and understand the world better. But, when it comes to things like learning outcomes or being equipped for a job, it’s hard to prove that is a skill.”

Kaily Garcia, Beaumont senior and English major, said she believes English majors should learn from both types of courses.

“I really enjoy the literature courses,” she said. “I think they’re a lot of fun. But, as someone who wants to work in the field of editing and writing, I like the skill-based courses. I think the literature electives make more sense if you’re going to go into graduate school or teaching. I wish I’d gotten to take more classes on skills and things that are related to a career.”

Garcia said she also sees the potential benefits and consequences of both approaches.

“English is kind of a tricky subject in terms of the move to more vocational courses,” she said. “English, traditionally, has been about studying ideas, how to communicate, literature, humanity as a whole and thinking on things. It’s harder and harder to make a living with that now than it has been in the past. I think that means the English degree is changing in general. It’s sad to see the more theoretical, literary, artistic side of English disappear, but I don’t think that means that there’s not value in the newer, more skill-based side.”

Daigrepont also acknowledged that the encouragement of literature courses may not be in the best interest of each student.

“I think the old-fashioned people like me, we see a student and we want them to pick an area to specialize in, and then go get a master’s degree, and then go get a Ph.D., and we’re not really thinking about their life,” he said. “Maybe that’s not what they want to do. The fact is, most of our master’s students, I think, want to teach in the secondary schools or even the primary schools, and they want to stay with their families. They don’t want to go off and live the life of a professor.”